JAMIE EDWARDS

I’ve heard it said before that doing art history from the books is easy. It was Prof. Mary Beard, Cambridge Classicist of A Don’s Life fame, that said it, who is married to Robin Cormack, the art historian. Now inasmuch as I’d say that doing art history from the books is only as easy as doing any humanities subject from the books, and that researching and putting together a coherent argument about art history is only as easy as doing the same in, say, History, English and, indeed, Classics(!) etc., I have a new-found empathy for Beard’s statement after this weekend.

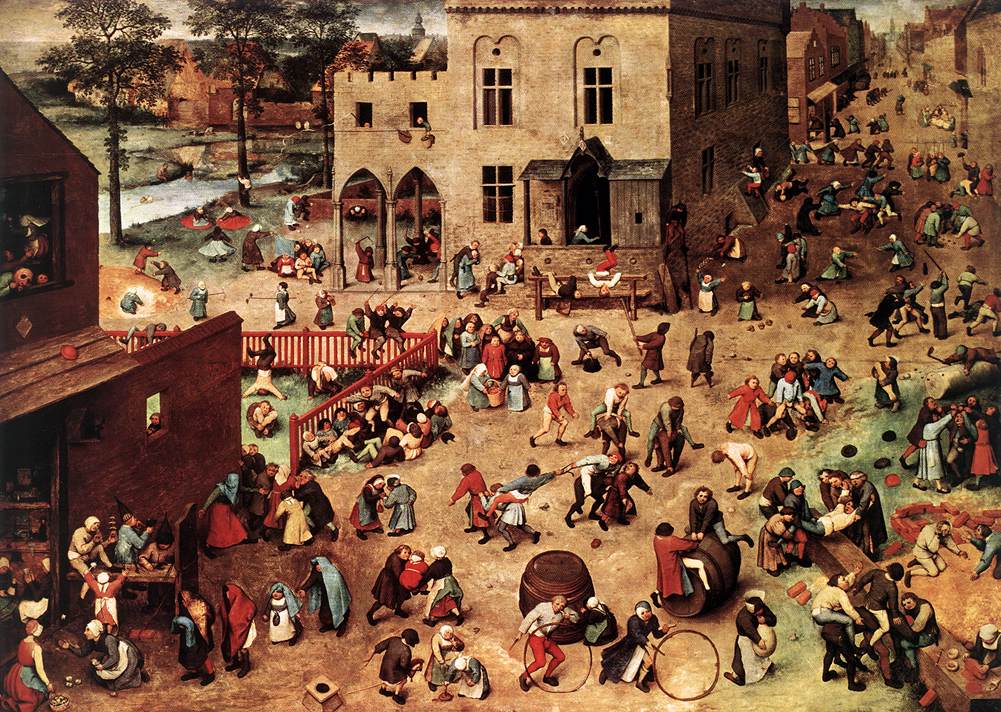

I’ve been in Vienna. My PhD’s on Pieter Bruegel’s paintings and the lion’s share of the surviving ones are displayed in Vienna at the Kunsthistoriches Museum. The Bruegels assembled here are the ones that were in the Habsburg Imperial collection, having been collected by Emperor Rudolf II and his brother the Archduke Ernst of Austria, who were both apparently dead keen on Bruegel’s art. It’s these (less the ones that the Habsburgs lost and are now elsewhere) that I came to see this weekend.

I wanted to put some of my thoughts–gleaned from hours pouring over the books and trawling JSTOR, etc., as well as looking at other Bruegels in Europe–to practice in front of the pictures themselves. And let’s just say that things quickly get tricky when you’re face-to-face with the things.

Take the Peasant Wedding Feast. Painted around 1568, the literature about this picture (and all of Bruegel’s peasants for that matter) usually says 1 of 2 things. 1 school of thought says that the peasants are emblems of sin, intended to represent drunken gluttony and supposedly put up on the wall to be seen by posh people who would renounce the peasantry and deplore their lack of table manners, keenness for booze etc. School of thought number 2, however, says that the peasants are emblems of fun, and that posh Antwerpers would have had a laugh at the peasants and their rustic, bumbling ways. According to this reading the pictures were looked at in lieu of actually going out into the countryside to mingle with the farmers, which wealthy Antwerp citizens were fond of doing in the mid-1500s.

The premise underlying both is that Bruegel’s peasants were looked at by people who were in no way themselves peasants. Panel paintings in general would indeed have been prohibitively expensive and well out of the reach of the poor in the sixteenth century. A fair amount of evidence also exists to permit the conclusion that Bruegel’s panels were especially pricey. Moreover, we’ve learned recently that the Peasant Wedding was probably owned by Jan Noirot, Master of the Antwerp Mint who was a member of Antwerp’s upwardly mobile, mercantile class and who had 5 Bruegels in total. And so it seems that the premise is correct: that peasants in (Bruegel’s) art weren’t looked at by the peasants.

But trying to figure out which of the moral or non-moral readings is closest to the mark when you’re looking at the Peasant Wedding proves impossible.

Are the wedding celebrants really gluttonous drunks? Sure, a couple swig from their big beer jugs in a way that makes them look like the sixteenth-century’s equivalent to the modern-day binge drinker, but where’s all the vomiting, falling over and fistycuffs that we see in older art showing the drunken fallout of a peasant wedding or kermis? Meanwhile, the food itself is pretty simple and I don’t reckon these peasants would ever have been accused, as was sometimes said of peasants at this time, of squandering their meagre earnings on lavish food that was above their station. Meanwhile, the bride herself looks positively demure, happy (well she is newly-wed after all!) but demure all the same. And what about the cute kid at the front eating with his fingers? Although some might think this is intended to say “the apple never falls far from the tree” and that the child has acquired the same bad habits and ill-manners as his elders, is it not simply the case that kids from all kinds of backgrounds eat with their fingers and that it never raises an eyebrow?

So you could say that the picture is fairly innocent. It hardly seems to be the case that Bruegel wanted to make a bad example out of the peasantry.

But at the same time, and turning to the other side of the debate, what’s actually funny about this picture? Although we might like to think that in the 1500s sensibilities were different and that they might have laughed at stuff we now don’t, there really is nothing outrageous happening in the Peasant Wedding that might have raised a smile, and there’s no pun being illustrated or funny gesture being performed that may have roused laughter. Looking at it today, I think it’s pretty naïve to think that Bruegel’s original audience found peasants implicitly funny irrespective of what they’re actually shown to be doing, which in this case is simply celebrating a wedding over beer and porridge. Proof again comes from older art. For example, look up Sebald Beham’s peasants and his images of them shitting and drunkenly canoodling. These may well have been funny (the scatological has always tended to induce laughter) but they’re funny in exaggerated ways that emphasise debauchery in ways that Bruegel’s are not.

And so the comic reading is as tough to swallow as the moral one.

In other words, the essential binary that has become the norm in investigations about Bruegel’s peasants falls apart when you scrutinise the pictures in reality. Standing in front of the Peasant Wedding today, I realised that while the picture may well have been owned by a well-to-do man (although Noirot did ultimately become bankrupt AND was implicated in a murder!) the ways we’ve approached understanding the pictures in this context hitherto is simply flawed. This is of course great, because it means there’s much left to say. But it is still a realisation that comes from confronting the picture in real life, devoid of an accompanying essay telling you this or that.

Equally perplexing are some of the other Bruegels. Is the nest robber in the Peasant and a Nest Robber really stealing from the bird’s nest? And what’s the peasant doing for that matter? Is he pointing? What at? And why? And why’s he stumbling headlong into a brook? The Suicide of Saul is simply weird because you can barely see the suicidal Saul and the picture’s dizzying amount of detail is even more staggering given the picture’s tiny dimensions – something you can only appreciate properly when you see it, because dimensions given in books fail to provide the same realisation. And what about the Children’s Games? Who was supposed to look at that? Why? What purpose does a picture showing kids playing serve? (Although you can read a good article about the last of these questions in the Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art, which is available online here.)

So Beard’s words apparently have a ring of truth in them – the abundant literature tells us this and that about Bruegel’s moral or not pictures, which we might at the time believe, but it seems difficult to give credence to either view when you’re actually in the Bruegel gallery in Vienna. This is of course an example of why seeing art in real life is so important: it forces you to think outside of what you’ve read and question some of the presumptions that sway your way of thinking about things. I’d already done this, of course (you don’t get a PhD by re-hashing all the old stuff), but seeing the pictures really brings it home.

Afterwards I popped to the Gemäldegalerie der Akademie der bildenden künste, which is a hop, skip and a jump away from the Kunsthistoriches. It’s basically the same set-up as the Barber (that is, it’s a picture gallery that’s part of an educational establishment, this time the fine art academy) and I went there to see Bosch’s Last Judgment, which he did probably at some time around 1500. A great thing that provoked a great many questions …!

[…] around as an object of discussion. All this just goes to show, as I’ve said before on this blog, that you really do stand to gain so much more from seeing all this stuff in real […]